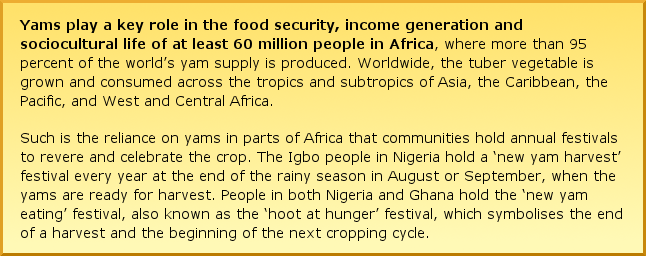

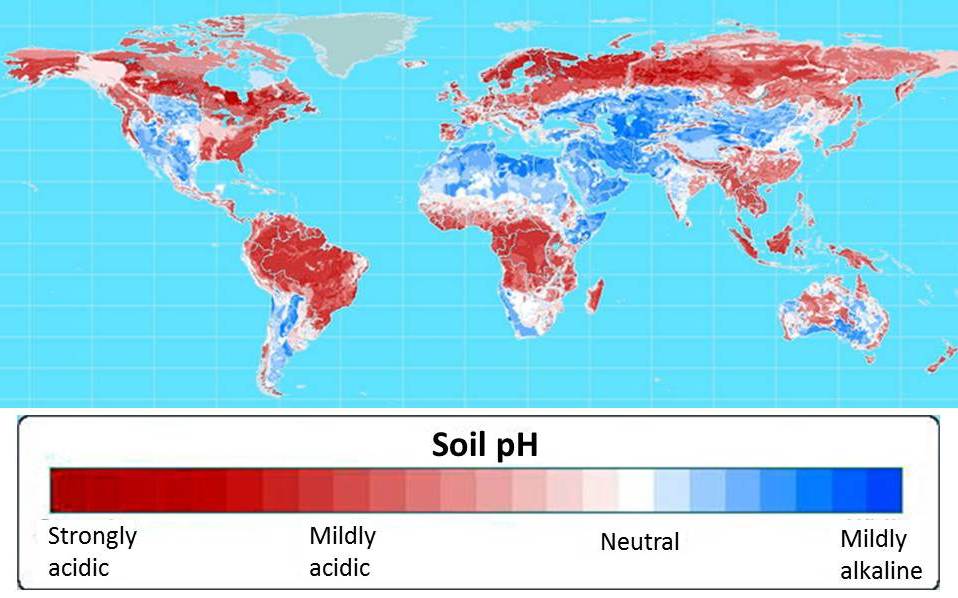

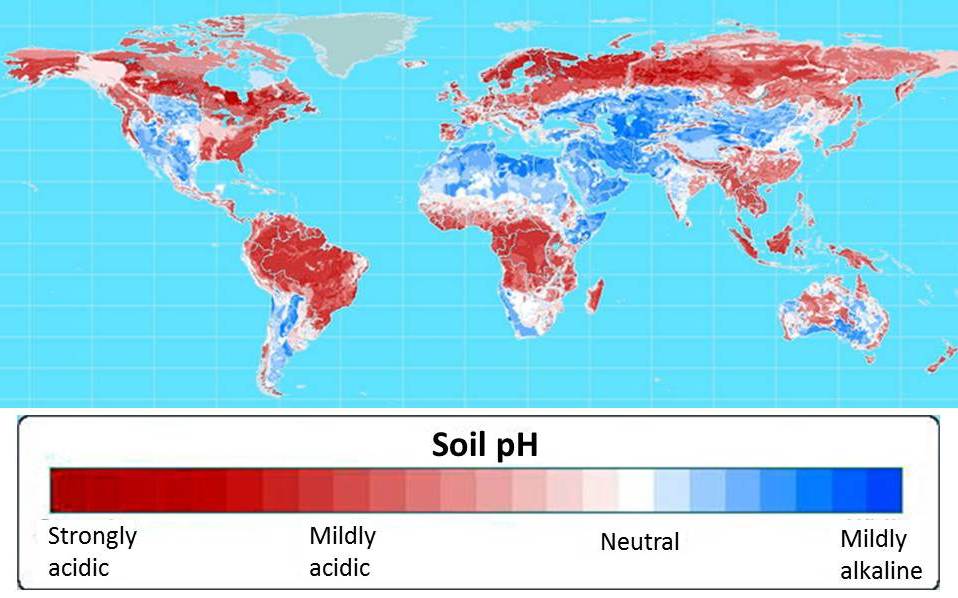

It’s a cruel feature of some of the most populous areas of the world, particularly in the tropics and subtropics: acid soils. They cover a third of the world’s total land area – including significant swathes of Africa, Asia and Latin America – and 60 percent of land we could use for growing food. Today around 30 percent of all arable land reaches levels of acidity that are toxic to crops.

Soil acidity occurs naturally in higher rainfall areas and varies according to the landscape and soil. But we also make the problem worse through intensive agricultural practices. The main cause of soil acidification is the overuse of nitrogen fertilisers, which farmers apply to crops to increase production. Ironically, the inefficient use of nitrogen fertiliser can instead make matters worse by decreasing the soil pH.

60 percent of the world’s potential crop-growing land is highly acidic. Map courtesy of Leon Kochian.

Acidity prevents crops from accessing the right balance of nutrients in the soil, limiting farmers’ yields. Its negative effect on world yield is second only to drought and is particularly hard felt by subsistent and smallholder farmers who cannot afford to correct soil pH using calcium-rich lime. As a result, these farmers are forced to grow less profitable, acid-tolerant crops like millet, or suffer huge yield losses when growing more popular cereal crops like wheat, rice or maize.

“In Kenya, acidic soils cover almost 90 percent of the maize-growing areas and can reduce yields by almost 60 percent,” says Samuel Gudu, Professor and Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Planning & Development) at Moi University in Kenya. “Farmers know that the soil affects their yields, but they still grow maize because it is so popular.”

As is true in many other sub-Saharan countries, maize is a staple of the Kenyan diet: the average Kenyan consumes 98 kilograms of it each year. But maize prices in Kenya are among the highest in Africa, which directly affects the poorest quarter of the population, who spend 28 percent of their income on the crop.

“Yield losses play a big part in this economic imbalance and are why we need affordable agronomic options to help our farmers improve yields,” says Samuel, who was a Principal Investigator of a GCP comparative genomics project which sought to provide some of these options.

A Kenyan farmer prepares her maize plot for planting. Acid soils cover almost 90 percent of Kenya’s maize-growing area, and can more than halve yields.

Aluminium toxicity and phosphorus deficiency: Public enemies number one and two in the fight against acidic soils

Between 2004 and 2014, crop researchers and plant breeders across five continents collaborated on several GCP projects to develop local varieties of maize, rice and sorghum that can withstand phosphorus deficiency and aluminium toxicity – two of the most widespread constraints leading to poor crop productivity in acidic soils.

Aluminium toxicity is the primary limitation on crop production for more than 30 percent of farmland in Southeast Asia and Latin America and approximately 20 percent in East Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and North America. Aluminium becomes more soluble in acid souls, creating a toxic glut of aluminium ions that damage roots and impair their growth and function. This results in reduced nutrient and water uptake, which in turn depresses yield.

Phosphorus deficiency is the next biggest soil deficiency after nitrogen to limit plant production. In acid soils, phosphorus is stuck (fixed) in forms that plants cannot take up. All plants need phosphorus to survive and thrive; it is a key element in plant metabolism, root growth, maturity and yield. Plants deficient in phosphorus are often stunted.

In a double whammy, the damage that aluminium toxicity causes to roots means that plants cannot efficiently access native soil phosphorus or even added phosphorus fertiliser – and adding phosphorus is an option that is rapidly becoming less viable.

“The world is running out of phosphorus as quickly as it is running out of oil,” says Leon Kochian, a Professor in the Departments of Plant Biology and Crop and Soil Science at Cornell University in the USA. “This is making its application a more expensive and less sustainable option for all farmers wanting to improve yields on acidic soils.” Indeed, the price of rock phosphate has more than doubled since 2007.

For 30 years, Leon has combined lecturing and supervising duties at Cornell University and the United States Department of Agriculture with his scientific quest to understand the genetic and physiological mechanisms that allow some cereals to tolerate acidic soils while others wither. And for the last 10 years, he has played an important leading role in GCP’s effort to develop new, higher yielding varieties of maize, rice and sorghum that tolerate acidic soils.

GCP builds on past crop breeding successes

The rationale behind GCP’s efforts stems from two independent and concurrent projects, which had been flourishing on different sides of the Pacific well before GCP was created.

One of those projects was co-led by Leon at Cornell University in collaboration with a previous PhD student of his, Jurandir Magalhães, at the Brazilian Corporation of Agricultural Research (EMBRAPA) Maize & Sorghum research centre.

Working on the understanding that the cells in grasses like barley and wheat use ‘membrane transporters’ to insulate themselves against excessive subsoil aluminium, Leon and Jurandir searched for a similar transporter in the cells of sorghum varieties that were known to tolerate aluminium.

“In wheat, when aluminium levels are high, these membrane transporters prompt organic acid release from the tip of the root,” explains Jurandir. “The organic acid binds with the aluminium ion, preventing it from entering the root.” Jurandir’s team found that in certain sorghum varieties, the gene SbMATE encodes a specialised organic acid transport protein, which stimulates the release of citric acid. They cloned the gene and found it was very active in aluminium-tolerant sorghum varieties. They also discovered that the activity of SbMATE increases the longer the plant is exposed to high levels of aluminium.

The rice variety on the left (IR-74) has the the gene locus Pup1, conferring phosphorus-efficient longer roots, while that on the right does not.

The other project, co-led by Matthias Wissuwa at Japan International Research Centre for Agricultural Sciences (JIRCAS) and Sigrid Heur at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in The Philippines, was looking for genes that could improve rice yields in phosphorus-deficient soils. They had already identified a gene locus (a section of the genome containing a collection of genes) that produced a protein which allowed rice varieties with to grow successfully in low-phosphorous conditions. The locus was termed ‘phosphorus uptake 1’ or Pup1 for short. With GCP support, the team were able to make the breakthrough of discovering the protein kinase gene responsible, PSTOL1 (‘phosphorus starvation tolerance 1’), and understanding its mechanism.

“In phosphorus-poor soils, this protein instructs the plant to grow larger, longer roots, which are able to forage through more soil to absorb and store more nutrients,” explains Sigrid, a plant geneticist at IRRI and a GCP Principal Investigator. “By having a larger root surface area, plants can explore a greater area in the soil and find more phosphorus than usual. It’s like having a larger sponge to absorb more water.”

Screening for phosphorus-efficient rice, able to make the best of low levels of available phosphorus, on an International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) experimental plot in the Philippines. Some types of rice have visibly done much better than others.

Leon clarifies that both projects were fairly advanced before they became part of the GCP fold. “Our team had already identified the gene SbMATE and were in the process of cloning it for breeding purposes. The IRRI and JIRCAS team had also identified Pup1 and were in the process of identifying and cloning the gene.”

The purpose of cloning these genes was to create molecular markers to help breeders identify whether the genes were present in the varieties they were working with. As an analogy, think of ‘reading’ a plant’s genome as you would read a story: the story’s words are the plant’s genes, and a molecular marker works as a text highlighter. Different markers can highlight or tag different keywords in the story. Tagging the location of beneficial genes in the DNA of plant genomes allows scientists to see which of the plants or seeds they are interested in – perhaps only a few out of hundreds or thousands – contain these genes. This forms the basis of marker-assisted breeding, which can help plant breeders halve the time it takes them to breed new high-yielding varieties for acidic soil conditions.

Leon says that GCP provided both projects with the opportunity to validate their discoveries and to use what they had found to develop new aluminium-tolerant sorghum varieties and phosphorus-efficient rice varieties for farmers. But it’s what happened next that made this GCP initiative unique.

Finding the best genes within the crop family

Sorghum, rice, maize and wheat are all part of the Poaceae (true grasses) family, evolving from a common grass ancestor 65 million years ago. Over this time, they have become very different from each other. However, at the genetic level they still have a lot in common.

Over the last 20 years, genetic researchers all over the world have been mapping these cereals’ genomes. These maps are now being used by geneticists and plant breeders to identify similarities and differences between the genes of different cereal species. This process is termed ‘comparative genomics’ and was a fundamental research theme for GCP during its second phase (2008–2014).

“The objective during GCP Phase I (2004-2007) was to study the genomes of important crops and identify genes conferring resistance or tolerance to various stresses, such as drought,” says Rajeev Varshney, Director of the Center of Excellence in Genomics at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT). “This research was long and intensive, but it set a firm foundation for the work in GCP’s second phase, which sought to use what we have learnt in the laboratory and apply it to breed better varieties of crops.”

Rajeev oversaw GCP’s comparative genomics research projects on aluminium tolerance and phosphorus deficiency in sorghum, maize and rice, as part of his GCP role as Leader of the Comparative and Applied Genomics Research Theme.

“The idea behind the sorghum, maize and rice initiative was to use the discoveries we had independently made in sorghum and rice to see if we could find the same genes in the other crop,” explains Rajeev. “In other words, we wanted to see if we could find PSTOL1 in sorghum and SbMATE in rice.”

Working together through a number of comparative genomics projects, the researchers were highly successful in reaching this goal, discovering valuable sister genes and beginning to introduce them into new improved crop varieties for farmers.

Extending research in sorghum and rice to maize

Researchers at Cornell and EMBRAPA had already been using similar comparative techniques to look for SbMATE in maize because of its close familial connection to sorghum. This research was overseen by Leon and another EMBRAPA researcher, Claudia Guimarães.

“We used the knowledge that Jurandir and Leon’s SbMATE project produced to prove that we had a major aluminium-tolerance gene,” reflects Claudia.

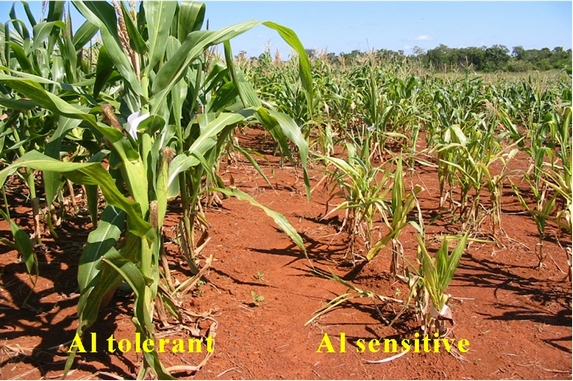

The SbMATE gene in sorghum explains about 80 percent of its aluminium tolerance, but Claudia says that in maize it explains only about 20 per cent, making it harder for researchers to find without a little help knowing what to look for. “So we had to dig a little deeper for other similar genes that confer aluminium tolerance, and we found ZmMATE.”

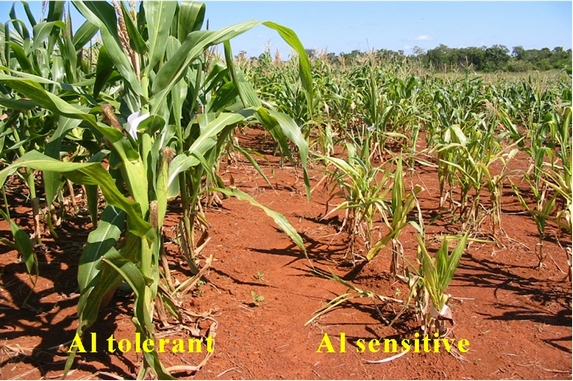

Maize trials in the field at EMBRAPA. The maize plants on the left are aluminium-tolerant while those on the right are not.

ZmMATE1 has a similar genetic sequence to SbMATE and encodes a similar protein membrane transporter that releases citric acid from the roots. Just as in sorghum, citric acid binds to aluminium in the soil, making it difficult for it to enter plant roots. The team have also discovered related gene ZmMATE2, which also encodes a transporter protein, but appears to confer aluminium tolerance via a different mechanism, as yet unclear.

Claudia has developed a number of molecular markers for ZmMATE, which have been successfully used by breeders at EMBRAPA as well as by African partners in Niger and Kenya, such as Samuel Gudu, to identify maize breeding lines that have the gene.

“We used aluminium-tolerant maize varieties sourced locally and from Brazil to develop a range of potential new varieties,” says Samuel. “The goal is to develop varieties that are suited to our environment and not too dissimilar to varieties that Kenyan farmers like to grow, except they have a higher tolerance to aluminium toxicity.”

Left to right (foreground): Leon Kochian, Jurandir Magalhães and Samuel Gudu examine crosses between Kenyan and Brazilian maize, at the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI), Kitale, in May 2010.

Involving farmers in the crop breeding process is an important part of such programs being successful, explains Samuel. “They help us identify maize varieties that they have observed have higher tolerance to acidic soils. We also try to incorporate other features that they want, such as disease resistance and higher yield. By incorporating their feedback into the breeding process they are more likely to grow any new varieties, as they have played a part in their development.”

Samuel says they have developed some local aluminium-tolerant varieties, which rank among the best for aluminium tolerance. Interestingly, these varieties seem to have a different aluminium-tolerance mechanism to the Brazilian varieties.

“From the work Samuel has done, we’ve possibly identified a novel source of aluminium tolerance in Kenyan maize varieties,” says Claudia. “We are now working together with Leon to identify the genes that are conferring this tolerance so we can develop markers to help Kenyan maize breeders also identify these varieties more efficiently.”

To help in the process, Samuel and his team are developing single-cross hybrids with a combination of both the novel Kenyan sources of aluminium tolerance and ZmMATE from Brazil, which will be even more tolerant to acidic soils.

Breeding for multiple stresses is a step-by-step process

Suradiyo, a farmer from Bojong Village near Yogyakarta, Indonesia, harvests rice.

In Asia, about 60 percent of rainfed rice is grown on soils that are affected by multiple stresses. These typically include phosphorus deficiency as well as aluminium toxicity, salinity and drought.

These stresses are particularly hard felt in Indonesia, which is the world’s third-largest rice producer. Joko Prasetiyono is a molecular rice breeder at the Indonesian Center for Agricultural Biotechnology and Genetic Resources Research and Development (ICABIOGRAD). His team have been collaborating with IRRI and JIRCAS for many years and contributed to validating the effect of Pup1 by embedding it into three popular local rice varieties – Dodokan, Situ Bagendit and Batur – which were then able to tolerate phosphorus-deficient conditions.

“The aim [with GCP research] was to breed varieties identical to those that farmers already know and trust, except that they have PSTOL1 and an improved ability to take up soil phosphorus,” says Joko.

Joko says that these varieties – which will be available in one to two years – will yield as well as, if not better than, traditional varieties, and will need 30–50 percent less fertiliser.

But the work is only partly finished for Joko and his Asian partners. They are now building on previous work done at Cornell and EMBRAPA to include the SbMATE gene in their varieties. “Higher yields will only be possible if the plant can also tolerate excess aluminium, which severely inhibits root growth and thereby water and nutrient uptake,” explains Joko. “We are also looking at incorporating salt-tolerance and drought-tolerance genes. It’s a step-by-step process where we hope to build tolerance to the multiple stresses that afflict most rice-growing areas throughout Asia and the world.”

Introducing PSTOL1 into maize and sorghum

At EMBRAPA, Claudia is also interested in building up tolerance to multiple stresses and was involved in the project to look for genes similar to PSTOL1 in maize. “As soon as IRRI and JIRCAS had cloned the gene and created markers, we started using the markers to search for the gene in maize, as Jurandir did in sorghum,” she says.

Women farmers in India bring home their sorghum harvest.

Finding genes that confer phosphorus-efficiency traits in maize and sorghum has been a more challenging project, according to Leon. “From the rice work, we knew a big part of phosphorus efficiency was to do with root architecture – you want to have shallow horizontal roots instead of roots that grow down, which is often the case in maize and sorghum,” he explains. “This is because there is less accessible phosphorus further down the soil profile.”

Observing root architecture is difficult in ordinary soil, so the team had to develop new ways to visualise the plants’ roots. They grew plants in a transparent nutrient gel, which they then photographed to create three-dimensional images of the root structure.

The team found sorghum and maize varieties that contained genes similar to PSTOL1 in rice, but which also have longer root systems that radiated outwards rather than downwards in gels with higher concentration of aluminium. “These observations helped validate multiple PSTOL1 regions in sorghum and maize, which we’ve been able to develop markers for to help breeders identify these traits more easily,” says Leon.

These markers have successfully been used by sorghum breeders in Brazil and Africa to identify phosphorus-efficient varieties. Maize breeders in both Brazil and Africa are expected to use similar markers to validate their varieties in 2015.

New sorghum varieties prove their worth in the field

Eva Weltzien is one Africa-based sorghum breeder who has benefited from these PSTOL1 and SbMATE markers. Based in Mali at ICRISAT, Eva and her team have been using the markers to select for aluminium-tolerant and phosphorus-efficient varieties and validating their performance in field trials across 29 environments in three countries in West Africa.

She says the markers have helped evolve the way they do their breeding. “Using molecular markers, we are able to identify whether the lines we are breeding have genes that confer the traits that we want,” explains Eva. “It has really revolutionised our breeding program and helped it make great progress in the past three to four years.”

In Mali, sorghum is an important staple crop. It is used to make tô (a thick porridge), couscous, and local beers. Part of its popularity is its adaptability to various climates – in Mali it is grown in very dry environments as well as in forest/rainforest zones. However, it is widely affected by acidic soils.

Sorghum farmers at work in the field in Mali.

“Low phosphorus availability is a key problem for farmers on the coast of West Africa, and breeding phosphorus-efficient crops to cope with these conditions has been a main objective of ICRISAT in West Africa for some time,” says Eva.

“We’ve had good results in terms of field trials. We have at least 20 lines we are field testing at the moment, which we selected from 1,100 lines that we tested under high and low phosphorous conditions.” Eva says that some of these lines could be released as new varieties as early as next year.

“Overall, we feel the GCP partnership with EMBRAPA and Cornell is enhancing our capacity here in Mali, and that we are closer to delivering more robust sorghum varieties that will help farmers and feed the ever-growing population in West Africa.”

Leon notes that the work by Eva in Mali and by other African partners in Niger and Kenya is imperative for the research. “Just because plants have these genes, doesn’t mean they will all display aluminium tolerance or phosphorus efficiency. You still need to test and observe for these traits in the field and determine what other factors might affect plants grown in acidic soils.”

One surprising observation that has Leon intrigued is a local sorghum variety with a phosphorus-efficiency gene that is close to where the SbMATE gene resides in the sorghum genome. “This suggests that SbMATE, which aids with aluminium tolerance, may also improve phosphorus efficiency. This means we could use SbMATE markers to look for both phosphorus efficiency and aluminium tolerance,” he says. Leon and Jurandir will continue to validate this result post-GCP.

Working together to improve food security worldwide

GCP’s comparative genomics projects have laid a significant foundation for further research into and breeding for tolerance to multiple plant stresses.

A Kenyan farmer in her maize field.

“We’re in a golden age of biology where we are learning more and more about the complexities and commonalities of plants, which is allowing us to manipulate them ever so slightly to help them tolerate multiple environmental stresses,” says Leon. “As a geneticist, I am extremely proud to be part of this, particularly seeing the potential impact that the basic research we do in the laboratory can have on crop improvement and the lives of people in poorer countries.”

Although not all projects produced new and improved varieties ready for release, they are well and truly in the pipeline. Each partner institute is committed to work together and source new funding to continue on their quest to produce further products.

“GCP has really installed in us a spirit to see this work through and expand on it,” says Leon. “I mean, we are now working with other countries and institutes to share what we have learnt with them and help them make the discoveries that we have. It’s a credit to GCP for bringing us all together; that was a key to the success of the project. Each partner has brought their expertise to the table – genomics, molecular biology, plant breeding – and it has been great to see the impact filter into Africa and Asia.”

In Kenya, Samuel agrees with Leon’s assessment. “GCP gave us an opportunity to build our expertise and start interacting with the rest of the world,” he says. “But more importantly, it means that we’re contributing to food security in Kenya, and that makes us really proud.”

Although the sun is setting on GCP, work on comparative genomics projects is still in progress, with all parties still working towards delivering important new acid-beating varieties to farmers.

A boy rides his bicycle next to a rice field in the Philippines. With acid soils affecting half the world’s current arable land, acid-beating crop varieties will help farmers feed their families – and the world – into the future.

More links