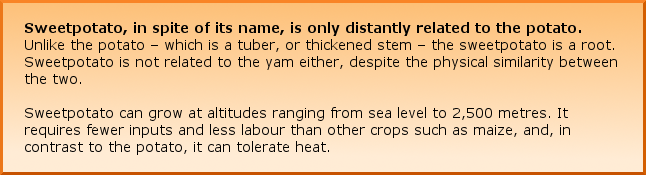

Farmer Maria Mtele holds recently harvested orange-fleshed sweetpotatoes in a field in Mwasonge, Tanzania.

Sweetpotato has a long history as a lifesaver. The Japanese used it when typhoons demolished their rice fields. It kept millions from starvation in famine-plagued China in the early 1960s and came to the rescue in Uganda in the 1990s, when a virus ravaged the cassava crop.

In sub-Saharan Africa, sweetpotato is proving crucial in the fight against blindness, disease and premature death among children under five. And, as agriculture becomes more market-oriented across the continent, sweetpotato has some significant advantages: it requires fewer inputs and less labour than other crops such as maize, tolerates marginal growing areas and can mature within four months.

On these fertile grounds, researchers across the globe are not underestimating the importance of sweetpotato as a staple crop.

“Yields achieved by resource-poor farmers in sub-Saharan Africa are typically low,” says Roland Schafleitner of the International Potato Center (CIP), based in Peru.

“Improved and well-adapted sweetpotato varieties with increased tolerance to drought, pests and diseases will have a positive impact on food and income security in sub-Saharan Africa and can significantly contribute to increasing productivity,” he says.

Roland was Principal Investigator of two research projects funded by the CGIAR Generation Challenge Programme (GCP), which developed genetic and genomic resources for breeding improved sweetpotato.

At the outset of the work, Roland says: “Breeding efforts were limited by the crop’s genetic complexity and the lack of information available about its genetic resources.

“It was clear that if we could develop genetic tools and make concerted efforts towards understanding the gene pool of sweetpotato, the breeding potential of the crop would improve.”

Sub-Saharan Africans getting their vitamin A from sweetpotato

Malnutrition does not always mean a simple lack of calories; research suggests that nutrient shortfalls are an even bigger killer. Vitamin A deficiency is a leading cause of blindness, infectious disease and premature death among children under five and pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

Sweetpotato comes in a wide range of colours. Varieties with dark orange flesh are naturally very rich in the pigment beta-carotene, which the body converts into vitamin A. However, the sweetpotatoes traditionally grown in Africa are pale-fleshed and low in beta-carotene. African consumers were not used to eating colourful sweetpotato – and these orange-fleshed varieties were in any case not well adapted African growing conditions.

Recent years have therefore seen a collaborative effort by researchers across the world to breed orange-fleshed sweetpotato varieties fortified with high levels of beta-carotene, and even enriched with other nutrients, that have also been crossed with local varieties and so are adapted to local conditions and tastes. A crucial part of these efforts has also been to create public awareness and encourage people to grow, eat and buy these new varieties.

Two cheeky young chappies from Mozambique enjoy the sweet taste of orange-fleshed sweetpotato rich in beta-carotene, or pro-vitamin A.

All of this adds to the growing momentum behind sweetpotato. The growing awareness of sweetpotato’s potential nutritional benefits for the poor and food insecure, as well as its value for subsistence farmers as a reliable crop that withstands drought and requires minimal inputs, mean that it is growing in significance.

Orange-fleshed sweetpotato can be used to make a variety of tasty products from doughnuts to chapati.

More than 95% of the world’s sweetpotato crop is grown in developing countries, where it is the fifth most important staple food crop. It is particularly important in many African countries: Madagascar in Southern Africa; Nigeria in West Africa; and those surrounding the Great Lakes in East and Central Africa – Uganda, Malawi, Angola and Mozambique.

According to 2013 figures from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 3.6 million hectares of sweetpotato were harvested in Africa. While the average global yield of sweetpotato per hectare was 14.8 tonnes, across all East African countries in 2013 it was only half this, at 7.1 tonnes per hectare. In West African nations the average yield was even worse, at 3.7 tonnes per hectare.

Farmers are unable to make the most of their crops because the varieties available to them, including traditional varieties (or landraces) have low resistance to viral diseases and insect pests, and poor tolerance to drought. It is therefore crucial that when developing new varieties breeders are able to efficiently incorporate pest and disease resistance and drought tolerance traits.

New DNA markers identified for sweetpotato disease

The sweetpotato virus disease (SPVD) is the most serious disease affecting sweetpotato in sub-Saharan Africa. It often causes serious yield losses of up to 80–90 percent.

The disease is the result of joint infection by two viruses: the sweetpotato feathery mottle virus and the sweetpotato chlorotic stunt virus. Of the two, the stunt virus is the more problematic.

Wolfgang Grüneberg, also from CIP, says that, in the years 2006–2008, 52 new DNA markers were developed as part of GCP-funded research to improve marker-assisted selection for resistance to the disease.

“The results,” says Wolfgang, Principal Investigator for the research, “looked promising for developing a large number of orange-fleshed sweetpotatoes with resistance to SPVD.”

Immediately following the development of the markers, two varieties of sweetpotato were developed using a cloned gene, Resistan, known to confer resistance to the virus. The first variety was used to improve an SPVD test system so that the disease could be diagnosed earlier if a crop was affected. The second variety underwent field tests in regions in Uganda that were highly affected by the disease.

Mobilising the genetic diversity of sweetpotato for breeding

The goals of the GCP-supported work were to develop a diverse genetic resource base for sweetpotato and stimulate the use of new tools in ongoing breeding programmes.

To help transfer this work from high-end laboratories to resource-poor research labs in developing countries, GCP promoted collaboration across institutions and borders. Researchers from Brazil, Mozambique, Uganda and Uruguay worked together on sweetpotato genetic research projects.

As Roland explains, the basic first steps needed to begin to ‘mobilise’ the genetic diversity of sweetpotato were developing a reference set of varieties and improving genomics tools to work with polyploid crops, i.e. those possessing multiple sets of chromosomes, such as sweetpotato.

GCP-supported researchers in Peru and sub-Saharan Africa defined a reference set of 472 varieties of sweetpotato, carefully selected and honed to represent both the diversity of the crop and its most important agronomical and nutritional traits.

“Based on a reference set, genetic markers can be developed that are associated with important characteristics of the crop and can help breeders to select favourable genotypes,” says Roland.

The gene sequences developed during the Programme are now available as a Sweetpotato Gene Index.

“Based on these sequences,” says Roland, “molecular markers have been designed that can help breeders and gene-bank curators to assess the genetic diversity of their accessions and to perform genetic mapping studies.

“Today, techniques that yield a much larger number of markers for genetic studies and selection are accessible for sweetpotato,” he says.

Mwanaidi Rhamdani (left) works with Maria Mtele in an orange-fleshed sweetpotato field in rural Tanzania.

The genetic lifelines reach Africa

Sweetpotato is one of the most important staple crops in Mozambique, ranking in third position after cassava and maize. The areas harvested in Mozambique in 2013 were 1.7 million hectares of maize, 780,000 hectares of cassava and 120,000 hectares of sweetpotato.

GCP funded breeders in Mozambique and Uganda to learn how to identify genetic markers that would prove useful for future sweetpotato breeding.

“Our African partners visited us at CIP and helped us complete the work on identifying markers,” recalls Roland. “This provided the opportunity for direct ‘technology transfer’ to breeders in the target region.”

The collaboration had, for the first time, created a critical amount of genetic and genomics resources for sweetpotato. The resulting Sweetpotato Gene Index and the new markers were published in a peer-reviewed journal, BMC Genomics (2010) 11:604.

The new genetic resources are in use at CIP in Peru and in breeding programmes in Burkina Faso, Mozambique, Uganda, Uruguay and the USA for the assessment of the genetic diversity of germplasm collections.

“The markers have been used for diversity analysis, especially at the CIP gene bank, and also in Africa,” says Roland, who says the markers will help future research.

“Such analysis guides germplasm conservation decisions, and diversity studies are a great tool to develop core collections and composite genotype sets – subsets of the whole collection – which allow for more practical screening for specific traits than large collections.”

More links

- Sweetpotato Gene Index

- For research and breeding products, see the GCP Product Catalogue and search for sweetpotatoes.