By 2050, the global demand for food will nearly double, numbers of farmers are predicted to decrease and the amount of suitable farmland is not expected to expand. To meet these challenges, farmers will rely on plant breeders becoming more efficient at producing crop varieties that are higher yielding and more resilient.

By 2050, the global demand for food will nearly double, numbers of farmers are predicted to decrease and the amount of suitable farmland is not expected to expand. To meet these challenges, farmers will rely on plant breeders becoming more efficient at producing crop varieties that are higher yielding and more resilient.

The Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP), established by the CGIAR Generation Challenge Programme (GCP), provides plant breeders with state-of-the-art, modern breeding tools and management techniques to increase agricultural productivity and breeding efficiency. Its work democratises and facilitates the adoption of these tools and techniques across world regions and economies, from emerging national programmes to well-established companies. In particular, it is helping to bridge the technological and scientific gap prevailing in developing countries by providing purpose-built informatics, capacity-building opportunities and crop-specific expertise to support the adoption of best practice by breeders, including the use of molecular technologies. This will help reduce the time and resources required to develop improved varieties for farmers.

IBP is certainly a winner for maize breeder Thanda Dhliwayo of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT): “IBP is the only publicly available integrated breeding data-management system. I see a lot of potential in increasing efficiency and genetic gain of public breeding programmes,” he says.

For Graham McLaren, who was GCP’s Bioinformatics and Crop Information Sub-Programme Leader, an informatics system is vital for advancing the adoption of modern breeding strategies and the use of molecular technologies.

“One of the biggest constraints to the successful deployment of molecular technologies in public plant breeding, especially in the developing world, is a lack of access to informatics tools to track samples, manage breeding logistics and data, and analyse and support breeding decisions,” says Graham, who is now IBP Deployment Manager for Eastern and Southern Africa.

This is why IBP was set up, explains Graham: “We want to put informatics tools in the hands of breeders – be they in the public or private sector, including small- and medium-scale enterprises – because we know they can make a huge difference.”

Handling big data

Knowledge is power, making data are almost a crucial a raw material for plant breeding as seeds. To make good choices about which plants to use, breeders need information from thousands of plant lines about a wide range plant of characteristics, usually collected during field trials or greenhouse experiments, in a process known as phenotyping. Effective information management is therefore critical in the success of a breeding programme. IBP tackles these crucial information management issues, and many of its current users are finding it invaluable for handling their phenotypic data. IBP also aims to facilitate the use of molecular-breeding techniques, which require genetic as well as phenotypic information (see box), and support users in integrating these into their breeding process.

The advent and implementation of molecular breeding has increased breeders’ efficiency and capacity to generate new varieties – although the inclusion of genetic data has also added to the amount of information that breeders need to handle.

“Prior to molecular breeding, we would record our observations of how plants performed in the field [phenotypic data] in a paper field book; we would either file the book away or re-enter the data into an Excel spreadsheet,” says Adeyemi (Yemi) Olojede, Assistant Director and Coordinator in charge of the Cassava Research Programme at the National Root Crops Research Institute (NRCRI) in Nigeria and Crop Database Manager for NRCRI’s GCP-funded projects.

“We still need to phenotype, but molecular-breeding techniques allow us to select for plant characteristics early in the breeding process by analysing the plant’s genotype to see if it has genes associated with desirable traits,” says Yemi. Groundwork is needed in order to make this possible: “This means we need to analyse the data of each plant’s genetic make-up as well as the phenotypic data so we can verify whether certain genes are responsible for the traits we observe.”

By using molecular markers to make certain which plants have useful genes right from the start – simply by testing a tiny bit of seed or seedling tissue – breeders and agronomists like Yemi can carefully select which ‘parent’ plants to use. These are then crossed in just the same way as in conventional breeding, but using only the most promising parents makes each generation is a much bigger step forward. Another advantage for breeders is that they do not necessarily have to grow all of the progeny from each set of crosses – usually thousands – all the way to maturity to see which plants have inherited the traits they are interested in.

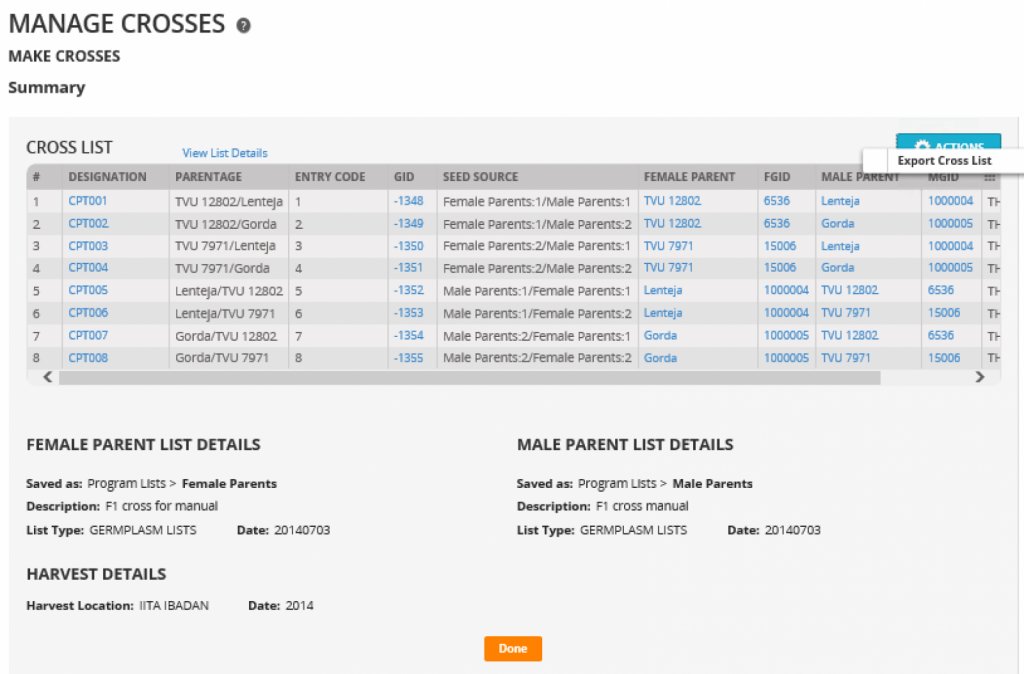

The IBP Breeding Management System makes it much easier for breeders to manage their data and make good use of both phenotypic and genotypic information. The Crossing Manager function facilitates the planning and tracking of crosses.

All of this makes breeding more efficient, reducing the time and cost associated with field trials and cutting the cumulative time it takes to breed new varieties by half or more. The end result is that farmers get the new crop varieties they need more quickly.

Keeping track of masses of information has always been a headache for breeders. However, the increased burden of data management that molecular breeding brings – together with the need to be able to carry out specialised genotypic analysis (study of the genetic make-up of an organism) – has proved to be a limitation for many public national breeding programmes such as NRCRI. These have consequently struggled to adopt molecular-breeding techniques as readily as the private sector.

Wanting to overcome this limitation as part of its mission to advance plant science and improve crops for greater food security in the developing world, in 2009 GCP gave Graham McLaren the momentous task of overseeing the development of the Integrated Breeding Platform.

Clearing the bottleneck

The IBP Web Portal provides information and access to services and crop-specific community spaces. These help breeders design and carry out integrated breeding projects, using conventional breeding methods combined with and enhanced by marker-assisted selection methods. The Portal also provides access to downloadable informatics tools, particularly the Breeding Management System (BMS).

While there are multiple analytical and data-management systems on the market for plant breeders, what sets the BMS apart is its availability to breeders in developing countries and its integrated approach. Within a single software suite, breeders are able to manage all their activities, from choosing which plants to cross to setting up field trials.

Graham explains that IBP has brought together all the basic tools that a breeder needs to carry out day-to-day logistics, data management and analysis, and decision support. “We’ve worked with different breeders to develop a whole suite of tools – the BMS – that can be configured to support their various needs,” explains Graham. “Having all the tools in one place allows breeders to move from one tool to the next during their breeding activities, without complex data manipulation. We’ve also set up the system for others to develop and share their tools, so that it can continue to grow with new innovative ideas.”

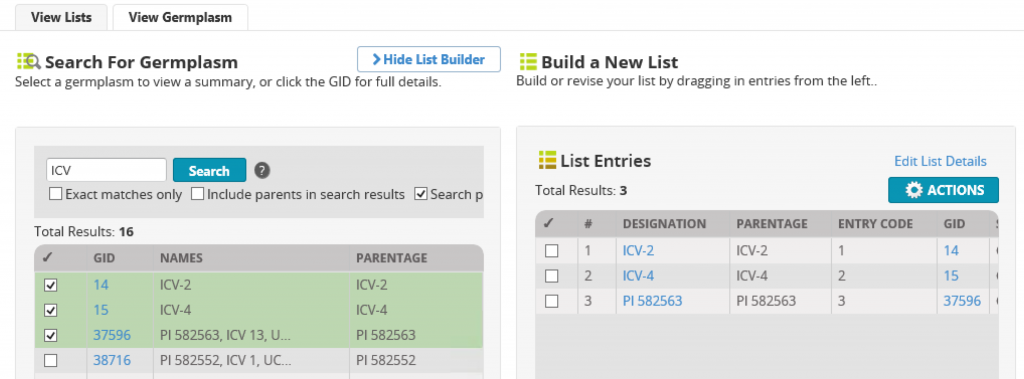

The IBP Breeding Management System has a complete range of interconnected tools. The Germplasm Lists Manager supports breeders in managing their sets of breeding materials.

Another feature of the Platform is that it provides breeders with access to genotyping services to allow them to do marker-assisted breeding. This is particularly useful for breeders in developing countries, who often don’t have the capacity to do this work. “It’s about giving all breeders the opportunity to enhance the way they do their job, without breaking the budget,” says Graham.

A unique and holistic component of IBP is the Platform’s community-focused tools. “IBP is as much about sharing knowledge as it is about managing data,” says Graham. “We’ve integrated social media to allow anybody with an interest in breeding, say, cowpeas, to join the cowpea community. They needn’t necessarily be a collaborator; they just have to have an interest in breeding cowpeas. They could read about what’s going on, contact people in the community and say ‘I’ve seen results for your trial. Could you send me some seed because I think it will do well in my region?’ or ‘Could you please further explain the breeding method you used?’ That’s what we hope to inspire with those communities.”

Graham concedes that this aspiration for the Platform has not yet been fully realised. However, he is hopeful that by providing training, coupled with the support from several key institutes and breeders, these communities will help to increase adoption of IBP and its tools.

“We are well aware that this Platform will be a big step for a lot of breeders out there, and they will need to invest time and patience into learning how to adapt it to their circumstances,” says Graham. “However, this short-term investment will save them time and money in the long term by making their process a lot more efficient.”

For Guoyou Ye, a senior scientist with the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), participating in IBP meant that he has gained a lot more understanding about the needs of breeders in developing countries for user-friendly tools.

“I started to spend time doing something for the resource-poor breeders. This has resulted in many invitations by breeding programmes in different countries to conduct training, and has given me a chance to establish a network for future work. I also had the chance to work with internationally well-known scientists and informatics specialists,” he says.

Providing help where it is needed

Yemi Olojede is another person who has been championing IBP, and his focus has been in Nigeria and other African countries. He spent time at GCP’s headquarters in Mexico in 2012 to sharpen his data-management skills and provide user insights on the cassava database. “I enjoy working with the IBP team,” says Yemi. “They pay attention to what we [agronomists and breeders] want and are determined to resolve the issues we raise.”

Yemi has also helped the IBP team run workshops for plant breeders throughout Africa.

He recounts that attendees were always fascinated by IBP and the BMS, but cautious about the effort required to learn how to use it. They were pleased, though, when they received step-by-step ‘how to’ manuals to help them train other breeders in their institutes, with additional support to be provided by IBP or Yemi’s team in Nigeria.

“We told them if they had any challenges, they could call us and we would help them,” says Yemi. “I feel this extra support is a good thing for the future of this project, as it will build confidence in the people we teach. They can then go back to their research institutes and train their colleagues, who are more likely to listen and learn from them than from someone else.”

IBP is continuing to run these training courses, through newly established regional hubs in Africa and Asia.

Mark Sawkins, IBP Deployment Manager for West and Central Africa, is helping to coordinate the formation and integration of the regional hubs within key agricultural institutes, including the Africa Rice Center in Benin, Biosciences Eastern and Central Africa (BecA) in Kenya, Centre d’étude régional pour l’amélioration de l’adaptation à la sécheresse (CERAAS) in Senegal, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS) in China, the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in India, the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) in Nigeria, and the National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (BIOTEC) in Thailand. Several further hubs are planned in additional countries, including in Latin America.

He says the hubs provide localised support in the use of IBP tools: “Their role is to champion IBP in their region,” says Mark. “They can take advantage of their established relationships and skills to help new users adopt the Platform. This includes providing education and training, technical support for IBP tools, and encouraging users to build their networks through the crop communities.”

Breeding rice and maize more efficiently using IBP

For Mounirou El-Hassimi Sow, a rice breeder from the Africa Rice Center, IBP is more than just a tool that helps him manage his data: “I’m seeing the whole world of rice breeders as a small village where I can talk to everyone,” he says.

“Through IBP, I have access to this great network of people, who I would never have met, who I can refer to when I have some challenges.”

Social networking tools are a novel feature incorporated into IBP to further develop the capacity of breeders like Mounirou. IBP hosts a number of crop-based and technical Communities of Practice that were established by GCP. These have nurtured relationships between breeders across different countries and organisations, encouraging knowledge sharing and support for young scientists.

Another way GCP has promoted and developed capacity to use IBP and molecular-breeding techniques is through training. Starting in April 2012, the Integrated Breeding Multiyear Course (IB–MYC) trained 150 plant breeders and technicians from Africa and Asia. The participants attended three two-week intensive face-to-face training workshops spread over three years, with assignments and ongoing support between sessions.

Roland Bocco (Africa Rice center, Benin), Dinesh K. Agarwal (ICAR, India) and Susheel K. Sarkar (ICAR, India) work together on a statistics assignment during their final workshop of the Integrated Breeding Multiyear Course (IB–MYC).

Mounirou participated in the course and says it provided him with the opportunity to learn more about molecular breeding and practice using the associated management and data analysis tools. “I had learnt about the tools in university and seen them on the Internet, but I did not know how to use them,” says Mounirou. “During the first year, we learnt about the theory and how the tools work. During the second and third years, we were comfortable enough with the tools to use our own data and troubleshoot this with the tutors. This was great and provided me with confirmation that these tools were applicable and useful for my work.”

Mounirou says he is now sharing what he learnt during the course with his co-workers and other plant breeders in Africa. “Since the Africa Rice Center became a regional hub for IBP, I’ve volunteered to help train rice breeders. It’s great to be able to share what I learnt and help them realise how this tool will help make their work so much easier.”

Another IB–MYC trainee, Murenga Geoffrey Mwimali, a maize breeder from the Kenya Agriculture and Livestock Research Organisation (KALRO), is also helping his networks to benefit from IBP. “When I returned from the training, I took the initiative to demonstrate the Platform to the management of my organisation, to show them that it is what we need to implement at the institute level. They were overwhelmingly positive, and we are working on running a training course for other researchers in the organisation to learn how to use the Platform.”

Jean-Marcel Ribaut, GCP and IBP Director, says these championing efforts are exactly what GCP and IBP were hoping IB–MYC would initiate. “By providing this initial intensive training to these selected participants, we felt this groundswell of capacity would slowly grow once they built their confidence,” says Jean-Marcel. “That young researchers like these feel they are competent and obligated to share what they learnt is a true credit to the product and the participants.”

From the GCP nest to world-scale deployment

IBP has been the single largest GCP investment. From 2009 to 2014, GCP allocated USD 22 million to the initiative, with financial support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the European Commission, the UK Department for International Development, CGIAR and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. This represented 15 percent of GCP’s entire budget.

Following GCP’s close in December 2014, IBP will continue to develop and improve over the next five years, with funding primarily originating from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. While the priority has been on informatics and service development in Phase I, the main focus of Phase II will be to concentrate on deployment and adoption. In the long term, the Platform is seeking further ongoing funding, and also looking into implementing some form of user-contribution for specialised or consulting services.

“We wanted to develop a tool to provide developing countries with access to modern breeding technologies, breeding materials and related information in a centralised and practical manner, which would help them adopt molecular-breeding approaches and improve their plant-breeding efficiency,” says Jean-Marcel. “I believe we have achieved this and at the same time built a tool that will prove very useful for commercial companies too. If we want the tool to continue to be affordable and sustainable for developing countries, then we have to look at ways of finding new sources of funding and of making revenue to offset the costs.”

Stewart Andrews, IBP Business Manager, is helping to make this happen.

“What we are looking at is a tiered membership system in the private sector, where enterprises would pay more the larger they are,” explains Stewart. “This would also be dependent on where in the world they are, with enterprises in Europe and North America contributing proportionately more financially than those in developing countries. This will help us to continue investing in our solutions while keeping them accessible to national programmes and universities in developing countries at little to no fee.”

For Jean-Marcel, creating a commercial stream for IBP services is a win for all parties. “If we are able to generate revenue we can not only provide sustainable support and offset the cost for poorer institutes, we can also continue to develop and improve the BMS software suite so that it becomes the tool of choice all over the world. In terms of social responsibility, the corporate world can play an essential role in this not only as donors but even more effectively as clients and users – adopting the BMS makes good business sense.”

Stewart says a sustainable income is vital for providing training and assistance. “We currently have about 7,000 researchers in the developing world who get this software for free, and each week we get 20–25 requests for help, assistance and training. This support costs money but is indispensable, particularly for those in the developing world who are trying to implement molecular breeding for the first time. You have to remember that this software is all part of a revolution in terms of plant breeding, so we need to provide as much assistance as we can if these breeders are going to buy into molecular breeding and all of its benefits.”

The IBP team is convinced that rolling out IBP will have a significant impact on plant breeding in developing countries.

Indeed, so far there have been more than 1,300 unique downloads of the BMS, with at least 250 early adopters worldwide using the software suite across their day-to-day breeding activities. The Platform’s strategy now builds on three regional teams (West and Central Africa, Eastern and Southern Africa, and South and South East Asia), each including experienced breeders and data managers. With the help of local representatives at seven well-established Regional Hubs to date (with more Hubs in development), this strategy has thus far yielded commitments from six African countries at the national level; from 24 Institutes spanning 58 breeding programmes at different stages of the adoption process; from 14 Universities where faculty members are using and/or teaching the BMS, partially or entirely; and from 134 “champions” engaged in the deployment plans and in supporting their peers.

“Because IBP has a very wide application, it will speed up crop improvement in many parts of the world and in many different environments. What this means is that new crop varieties will be developed in a more rapid and therefore more efficient manner,” concludes Graham.

![Breeders and researchers rate the Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP) “IBP is an important tool in current and future enhancement of national breeding programmes.” –– Hesham Agrama, Soybean Breeder, International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Zambia “The tools being developed with IBP will form the basis of crop information management at the Semiarid Prairie Agricultural Research Centre [SPARC] and other Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research centres.” –– Shawn Yates, Quantitative Genetics Technician, SPARC, Canada “We have successfully integrated IBP with our lentil programme and also included IBP in the training that we conduct regularly for the benefit of our partners in national agricultural research systems.” –– Shiv Agrawal, lentil breeder, International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, Syria “Our institute has embraced use of the Breeding Management System and IBP, and we are already seeing results in improved data management within the Seed Co group research function.” –– Lennin Musundire, senior maize breeder, Seed Co Ltd, Zimbabwe](http://www.generationcp.org/sunsetblog/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/ibp-2.png)